第三届“天下”会议——行星秩序下的最小限度道德:多元文化的视角

THEME OF THE CONFERENCE

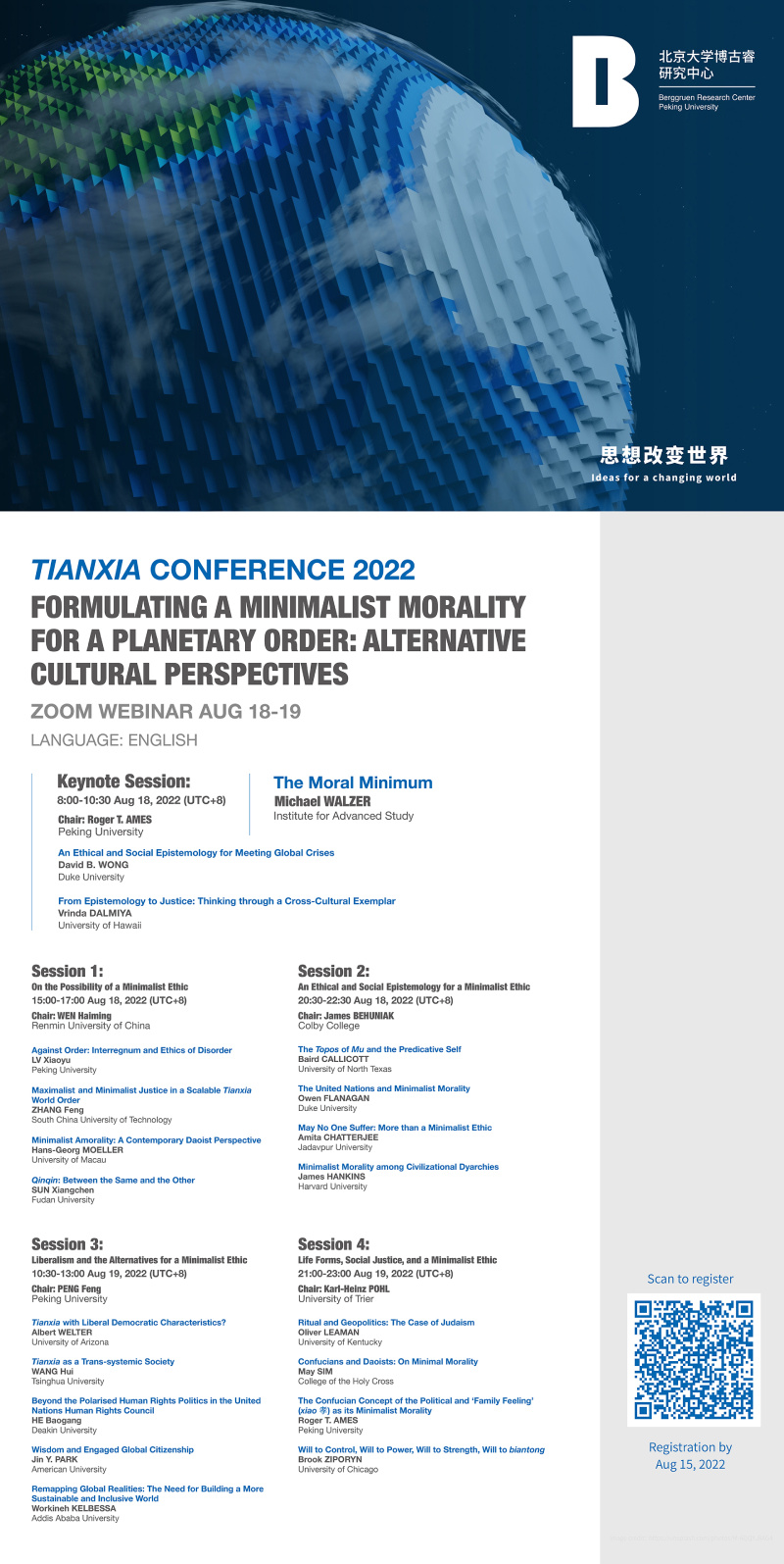

Formulating a Minimalist Morality for a Planetary Order: Alternative Cultural Perspectives

LANGUAGE

English

REGISTRATION

In order to attend the Conference, please complete this Zoom Webinar registration by August 15th, 2022

CONFERENCE AGENDA

Keynote Session:

The Moral Minimum

8:00-10:30 Aug 18, 2022 (UTC+8)

Keynote Speaker: Michael WALZER, Institute for Advanced Study

Chair: Roger T. AMES, Peking University

An Ethical and Social Epistemology for Meeting Global Crises

David B. WONG

Duke University

From Epistemology to Justice: Thinking through a Cross-Cultural Exemplar

Vrinda DALMIYA

University of Hawaii

Session 1:

On the Possibility of a Minimalist Ethic

15:00-17:00 Aug 18, 2022 (UTC+8)

Chair: WEN Haiming, Renmin University of China

Against Order: Interregnum and Ethics of Disorder

LV Xiaoyu

Peking University

Maximalist and Minimalist Justice in a Scalable Tianxia World Order

ZHANG Feng

South China University of Technology

Minimalist Amorality: A Contemporary Daoist Perspective

Hans-Georg MOELLER

University of Macau

Qinqin: Between the Same and the Other

SUN Xiangchen

Fudan University

Session 2:

An Ethical and Social Epistemology for a Minimalist Ethic

20:30-22:30 Aug 18, 2022 (UTC+8)

Chair: James BEHUNIAK, Colby College

The Topos of Mu and the Predicative Self

Baird CALLICOTT

University of North Texas

The United Nations and Minimalist Morality

Owen FLANAGAN

Duke University

May No One Suffer: More than a Minimalist Ethic

Amita CHATTERJEE

Jadavpur University

Minimalist Morality among Civilizational Dyarchies

James HANKINS

Harvard University

Session 3:

Liberalism and the Alternatives for a Minimalist Ethic

10:30-13:00 Aug 19, 2022 (UTC+8)

Chair: PENG Feng, Peking University

Tianxia with Liberal Democratic Characteristics?

Albert WELTER

University of Arizona

Tianxia as a Trans-systemic Society

WANG Hui

Tsinghua University

Beyond the Polarised Human Rights Politics in the United Nations Human Rights Council

HE Baogang

Deakin University

Wisdom and Engaged Global Citizenship

Jin Y. PARK

American University

Remapping Global Realities: The Need for Building a More Sustainable and Inclusive World

Workineh KELBESSA

Addis Ababa University

Session 4:

Life Forms, Social Justice, and a Minimalist Ethic

21:00-23:00 Aug 19, 2022 (UTC+8)

Chair: Karl-Heinz POHL, University of Trier

Ritual and Geopolitics: The Case of Judaism

Oliver LEAMAN

University of Kentucky

Confucians and Daoists: On Minimal Morality

May SIM

College of the Holy Cross

The Confucian Concept of the Political and ‘Family Feeling’ (xiao 孝) as its Minimalist Morality

Roger T. AMES

Peking University

Will to Control, Will to Power, Will to Strength, Will to biantong

Brook ZIPORYN

University of Chicago

CLICK THE COVER DOWNLOAD CONFERENCE HANDBOOK

CONFERENCE CONCEPT

One might argue the success of any conference series is not determined as much by providing answers to a given question as it is in clarifying the further direction of an intelligent conversation.

We in our present world are living in apocalyptic times in which the pandemic is ravaging humanity, and extreme weather events have become the new normal. Today, the Westphalian modern state system of equal, sovereign nations is the prevailing understanding of international relations. According to contemporary philosopher Zhao Tingyang, since the Westphalian model begins with the nation state, it is not a true “world order.” Instead, it is a global system of competing nation-states that with each nation seeking its own interests draws the world toward an international anarchy. Some nations dominate others, where this domination is enabled and exacerbated by the perspectives such a model generates, namely nationalism and racism.

This zero-sum game of winners and losers at an international level has proven to be wholly ineffective in addressing the pressing issues of our times where the pandemic is only the first among many crises we face: global warming, environmental degradation, income inequities, food and water shortages, massive species extinction, proxy wars, global hunger, and so on. The issues defining this human predicament are themselves organically interrelated, and unless they are addressed in a wholesale manner, there can be no effective resolution. Traversing any and all national, ethnic, and religious boundaries, this perfect storm can only be engaged and weathered effectively by a global village working collaboratively for the good of the world community as a whole.

By contrast with the Westphalian model, Zhao argues a starting point for thinking about the world in classical Chinese texts and its historical tradition was tianxia, a term he sees as signifying the entire world and thus “viewing the world as a world.” Zhao believes by conceptualizing international relations from the planetary perspective of tianxia, we can develop a sense of “worldness” instead of “internationality,” and that this can lead to a less divisive world order.

The two most important lines of critique that have emerged in two previous conferences with respect to Zhao Tingyang’s tianxia theory are 1) his tianxia system is self-consciously a purely rational endeavor that lacks a vision for its practical implementation in the real world, and 2) as a political economy it conspicuously and again self-consciously avoids any engagement with non-utilitarian ethics. With this critique in mind, the next conference of Berggruen China Center’s tianxia program will set as its primary objective the search for possible practical and ethical dimensions that can build upon Zhao’s theoretical work on tianxia as a planetary sense of “worldness.” The fundamental premise here is that in order for the tianxia system to remain relevant and significant in the world today and in our vision for a global future, it must at once acknowledge the plurality of moral ideals defining of the world’s cultures while at the same time seek practical ways to formulate a shared morality that can provide the limited solidarity needed to bring the world’s people together.

In this spirit, Michael Walzer in his Thick and Thin: Moral Argument at Home and Abroad wants “to endorse the politics of difference and, at the same time, to describe and defend a certain sort of universalism.” His claim is that “there are the makings of a thin and universalist morality inside every thick and particularist morality.” Again, Walzer insists that “minimalist meanings are embedded in the maximal morality, expressed in the same idiom, sharing the same (historical/cultural/religious/political) orientation.” He makes a good argument that moral minimalism in the formulation of all thick moralities is not foundational as “a common idea or principle or set of ideas and principles” and thus the same in every case. Nor is it some commonality at the end point of cultural differences. It cannot be reduced to generalizable procedures or generative rules of engagement. And as for the substance of thin morality, importantly for Walzer, such minimalism does not mean minor or emotionally shallow morality; on the contrary, thin and intensity come together as “morality close to the bone.”

For Walzer himself, his candidate for this thin morality would be “a common, garden variety kind of justice.” Other philosophers within the “thick” liberal morality would undoubtedly appeal to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as their basis for universalist ethic. However, for Robert Solomon and Elizabeth Wolgast, still within the liberal camp, humankind develops a sense of what is moral not from the application of some abstract ideal, but practically and incrementally from earliest childhood in our families in the feelings we share as we respond to perceived instances of immorality. The growth of moral meaning and behavior takes place locally in the ecologies of family and community.

Turning to alternative traditions, if we begin from the fact that the population of China is almost twice that of a combined eastern and western Europe, we can appreciate the scale of the diversity that has been pursued over the millennia among so many disparate peoples, languages, ways of life, modes of governance, and so on. While this diversity is truly profound, there seems to have been enough of a shared minimalist morality to hold it together as a continuous civilization and history for four thousand years and counting. Zhao Tingyang argues the shared identity that has provided the “continuity in change” (biantong 变通) over time lies in the written Chinese character and the classics engendered from this writing system. But what is missing in Zhao’s story is an account of the minimalist morality not only as it has been made explicit in these canonical texts, but also as it has been practiced across the centuries. Tacking in the same direction as Solomon and Wolgast, Confucian ethics takes the cluster of terms surrounding “family reverence” (xiao 孝) as the prime moral imperative that has made family feeling not only the explanation of its minimalist morality, but also the root and the substance of the living Confucian social, political, and global order.

When we move from liberal and Confucian thinking on a minimalist ethic to include other cultural traditions—Buddhist, Indian, Islamic, Ubuntu, Japanese, European, Jewish, and so on—how would they formulate an answer to the contemporary challenge of a fragmented and failing Westphalian “internationality” to reconceive of the world as a world? What would they offer as their conception of the shared and practicable morality so sorely needed at a planetary scale?

HOST

Berggruen Research Center, Peking University | Ideas for a changing world

The Berggruen Research Center, Peking University is a hub for East-West research and dialogue dedicated to the cross-cultural and interdisciplinary study of the transformations affecting humanity. Intellectual themes focus on frontier technologies and society—specifically in artificial intelligence, the microbiome and gene editing as well as issues involving global governance and globalization.

Conference playback👇

Michael Walzer on the Moral Minimum | Tianxia III 2022

Lv Xiaoyu on Against Order | Tianxia III 2022

Hans-Georg Moeller on Minimalist Amorality | Tianxia III 2022

Sun Xiangchen on Qinqin: Between the Same and the Other | Tianxia III 2022

Vrinda Dalmiya: From Epistemology to Justice | Tianxia III 2022

David Wong on An Ethical and Social Epistemology | Tianxia III 2022

Zhang Feng on Maximalist And Minimalist Justice | Tianxia III 2022

Wang Hui on Tianxia as a Trans-systemic Society | Tianxia III 2022

Albert Welter on Tianxia with Liberal Democratic Characteristics | Tianxia III

Jin Y. Park on Wisdom and Engaged Global Citizenship | Tianxia III 2022

Workineh Kelbessa on Remapping Global Realities | Tianxia III 2022

Baird Callicott on The Topos of Mu and the Predicative Self | Tianxia III 2022

Owen Flanagan on The United Nations and Minimalist Morality | Tianxia III 2022

Amita Chatterjee on “May No One Suffer” | Tianxia III 2022

James Hankins on Minimalist Morality among Civilizational Dyarchies | Tianxia III 2022

Oliver Leaman on Ritual and Geopolitics | Tianxia III 2022

May Sim on Confucians and Daoists | Tianxia III 2022

Roger Ames on The Confucian Concept of the Political and ‘Family Feeling’

Brook Ziporyn:Will to Control, Will to Power, Will to Strength, Will to biantong

Baogang He on Beyond the Polarized Human Rights Politics in the UNHRC

简介

活动主办方:

活动时间:

2022-08-18

活动地点:

Zoom线上会议

活动状态:

已结束

视频

第三届“天下”会议——行星秩序下的最小限度道德:多元文化的视角

THEME OF THE CONFERENCE

Formulating a Minimalist Morality for a Planetary Order: Alternative Cultural Perspectives

LANGUAGE

English

REGISTRATION

In order to attend the Conference, please complete this Zoom Webinar registration by August 15th, 2022

CONFERENCE AGENDA

Keynote Session:

The Moral Minimum

8:00-10:30 Aug 18, 2022 (UTC+8)

Keynote Speaker: Michael WALZER, Institute for Advanced Study

Chair: Roger T. AMES, Peking University

An Ethical and Social Epistemology for Meeting Global Crises

David B. WONG

Duke University

From Epistemology to Justice: Thinking through a Cross-Cultural Exemplar

Vrinda DALMIYA

University of Hawaii

Session 1:

On the Possibility of a Minimalist Ethic

15:00-17:00 Aug 18, 2022 (UTC+8)

Chair: WEN Haiming, Renmin University of China

Against Order: Interregnum and Ethics of Disorder

LV Xiaoyu

Peking University

Maximalist and Minimalist Justice in a Scalable Tianxia World Order

ZHANG Feng

South China University of Technology

Minimalist Amorality: A Contemporary Daoist Perspective

Hans-Georg MOELLER

University of Macau

Qinqin: Between the Same and the Other

SUN Xiangchen

Fudan University

Session 2:

An Ethical and Social Epistemology for a Minimalist Ethic

20:30-22:30 Aug 18, 2022 (UTC+8)

Chair: James BEHUNIAK, Colby College

The Topos of Mu and the Predicative Self

Baird CALLICOTT

University of North Texas

The United Nations and Minimalist Morality

Owen FLANAGAN

Duke University

May No One Suffer: More than a Minimalist Ethic

Amita CHATTERJEE

Jadavpur University

Minimalist Morality among Civilizational Dyarchies

James HANKINS

Harvard University

Session 3:

Liberalism and the Alternatives for a Minimalist Ethic

10:30-13:00 Aug 19, 2022 (UTC+8)

Chair: PENG Feng, Peking University

Tianxia with Liberal Democratic Characteristics?

Albert WELTER

University of Arizona

Tianxia as a Trans-systemic Society

WANG Hui

Tsinghua University

Beyond the Polarised Human Rights Politics in the United Nations Human Rights Council

HE Baogang

Deakin University

Wisdom and Engaged Global Citizenship

Jin Y. PARK

American University

Remapping Global Realities: The Need for Building a More Sustainable and Inclusive World

Workineh KELBESSA

Addis Ababa University

Session 4:

Life Forms, Social Justice, and a Minimalist Ethic

21:00-23:00 Aug 19, 2022 (UTC+8)

Chair: Karl-Heinz POHL, University of Trier

Ritual and Geopolitics: The Case of Judaism

Oliver LEAMAN

University of Kentucky

Confucians and Daoists: On Minimal Morality

May SIM

College of the Holy Cross

The Confucian Concept of the Political and ‘Family Feeling’ (xiao 孝) as its Minimalist Morality

Roger T. AMES

Peking University

Will to Control, Will to Power, Will to Strength, Will to biantong

Brook ZIPORYN

University of Chicago

CLICK THE COVER DOWNLOAD CONFERENCE HANDBOOK

CONFERENCE CONCEPT

One might argue the success of any conference series is not determined as much by providing answers to a given question as it is in clarifying the further direction of an intelligent conversation.

We in our present world are living in apocalyptic times in which the pandemic is ravaging humanity, and extreme weather events have become the new normal. Today, the Westphalian modern state system of equal, sovereign nations is the prevailing understanding of international relations. According to contemporary philosopher Zhao Tingyang, since the Westphalian model begins with the nation state, it is not a true “world order.” Instead, it is a global system of competing nation-states that with each nation seeking its own interests draws the world toward an international anarchy. Some nations dominate others, where this domination is enabled and exacerbated by the perspectives such a model generates, namely nationalism and racism.

This zero-sum game of winners and losers at an international level has proven to be wholly ineffective in addressing the pressing issues of our times where the pandemic is only the first among many crises we face: global warming, environmental degradation, income inequities, food and water shortages, massive species extinction, proxy wars, global hunger, and so on. The issues defining this human predicament are themselves organically interrelated, and unless they are addressed in a wholesale manner, there can be no effective resolution. Traversing any and all national, ethnic, and religious boundaries, this perfect storm can only be engaged and weathered effectively by a global village working collaboratively for the good of the world community as a whole.

By contrast with the Westphalian model, Zhao argues a starting point for thinking about the world in classical Chinese texts and its historical tradition was tianxia, a term he sees as signifying the entire world and thus “viewing the world as a world.” Zhao believes by conceptualizing international relations from the planetary perspective of tianxia, we can develop a sense of “worldness” instead of “internationality,” and that this can lead to a less divisive world order.

The two most important lines of critique that have emerged in two previous conferences with respect to Zhao Tingyang’s tianxia theory are 1) his tianxia system is self-consciously a purely rational endeavor that lacks a vision for its practical implementation in the real world, and 2) as a political economy it conspicuously and again self-consciously avoids any engagement with non-utilitarian ethics. With this critique in mind, the next conference of Berggruen China Center’s tianxia program will set as its primary objective the search for possible practical and ethical dimensions that can build upon Zhao’s theoretical work on tianxia as a planetary sense of “worldness.” The fundamental premise here is that in order for the tianxia system to remain relevant and significant in the world today and in our vision for a global future, it must at once acknowledge the plurality of moral ideals defining of the world’s cultures while at the same time seek practical ways to formulate a shared morality that can provide the limited solidarity needed to bring the world’s people together.

In this spirit, Michael Walzer in his Thick and Thin: Moral Argument at Home and Abroad wants “to endorse the politics of difference and, at the same time, to describe and defend a certain sort of universalism.” His claim is that “there are the makings of a thin and universalist morality inside every thick and particularist morality.” Again, Walzer insists that “minimalist meanings are embedded in the maximal morality, expressed in the same idiom, sharing the same (historical/cultural/religious/political) orientation.” He makes a good argument that moral minimalism in the formulation of all thick moralities is not foundational as “a common idea or principle or set of ideas and principles” and thus the same in every case. Nor is it some commonality at the end point of cultural differences. It cannot be reduced to generalizable procedures or generative rules of engagement. And as for the substance of thin morality, importantly for Walzer, such minimalism does not mean minor or emotionally shallow morality; on the contrary, thin and intensity come together as “morality close to the bone.”

For Walzer himself, his candidate for this thin morality would be “a common, garden variety kind of justice.” Other philosophers within the “thick” liberal morality would undoubtedly appeal to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as their basis for universalist ethic. However, for Robert Solomon and Elizabeth Wolgast, still within the liberal camp, humankind develops a sense of what is moral not from the application of some abstract ideal, but practically and incrementally from earliest childhood in our families in the feelings we share as we respond to perceived instances of immorality. The growth of moral meaning and behavior takes place locally in the ecologies of family and community.

Turning to alternative traditions, if we begin from the fact that the population of China is almost twice that of a combined eastern and western Europe, we can appreciate the scale of the diversity that has been pursued over the millennia among so many disparate peoples, languages, ways of life, modes of governance, and so on. While this diversity is truly profound, there seems to have been enough of a shared minimalist morality to hold it together as a continuous civilization and history for four thousand years and counting. Zhao Tingyang argues the shared identity that has provided the “continuity in change” (biantong 变通) over time lies in the written Chinese character and the classics engendered from this writing system. But what is missing in Zhao’s story is an account of the minimalist morality not only as it has been made explicit in these canonical texts, but also as it has been practiced across the centuries. Tacking in the same direction as Solomon and Wolgast, Confucian ethics takes the cluster of terms surrounding “family reverence” (xiao 孝) as the prime moral imperative that has made family feeling not only the explanation of its minimalist morality, but also the root and the substance of the living Confucian social, political, and global order.

When we move from liberal and Confucian thinking on a minimalist ethic to include other cultural traditions—Buddhist, Indian, Islamic, Ubuntu, Japanese, European, Jewish, and so on—how would they formulate an answer to the contemporary challenge of a fragmented and failing Westphalian “internationality” to reconceive of the world as a world? What would they offer as their conception of the shared and practicable morality so sorely needed at a planetary scale?

HOST

Berggruen Research Center, Peking University | Ideas for a changing world

The Berggruen Research Center, Peking University is a hub for East-West research and dialogue dedicated to the cross-cultural and interdisciplinary study of the transformations affecting humanity. Intellectual themes focus on frontier technologies and society—specifically in artificial intelligence, the microbiome and gene editing as well as issues involving global governance and globalization.

Conference playback👇

Michael Walzer on the Moral Minimum | Tianxia III 2022

Lv Xiaoyu on Against Order | Tianxia III 2022

Hans-Georg Moeller on Minimalist Amorality | Tianxia III 2022

Sun Xiangchen on Qinqin: Between the Same and the Other | Tianxia III 2022

Vrinda Dalmiya: From Epistemology to Justice | Tianxia III 2022

David Wong on An Ethical and Social Epistemology | Tianxia III 2022

Zhang Feng on Maximalist And Minimalist Justice | Tianxia III 2022

Wang Hui on Tianxia as a Trans-systemic Society | Tianxia III 2022

Albert Welter on Tianxia with Liberal Democratic Characteristics | Tianxia III

Jin Y. Park on Wisdom and Engaged Global Citizenship | Tianxia III 2022

Workineh Kelbessa on Remapping Global Realities | Tianxia III 2022

Baird Callicott on The Topos of Mu and the Predicative Self | Tianxia III 2022

Owen Flanagan on The United Nations and Minimalist Morality | Tianxia III 2022

Amita Chatterjee on “May No One Suffer” | Tianxia III 2022

James Hankins on Minimalist Morality among Civilizational Dyarchies | Tianxia III 2022

Oliver Leaman on Ritual and Geopolitics | Tianxia III 2022

May Sim on Confucians and Daoists | Tianxia III 2022

Roger Ames on The Confucian Concept of the Political and ‘Family Feeling’

Brook Ziporyn:Will to Control, Will to Power, Will to Strength, Will to biantong

Baogang He on Beyond the Polarized Human Rights Politics in the UNHRC

简介

活动主办方:

活动时间:

2022-08-18

活动地点:

Zoom线上会议

活动状态:

已结束

视频